Graham's number - big numbers blow my mind!

What's the biggest number you can think of? A million? A billion? The number of atoms in the observable universe (roughly \(10^{80}\))? Whatever you're imagining, I promise you it's basically zero compared to Graham's number—a number so incomprehensibly vast that it broke mathematics' ability to write things down.

For a while, Graham's number held the Guinness World Record as the largest number ever used in a serious mathematical proof. That title has since been claimed by even more mind-melting numbers (more on that later), but Graham's number remains legendary—a monument to just how weird infinity-adjacent mathematics can get.

Meet Ronald Graham: The Juggling Mathematician

Before we dive into the number, let's meet its creator. Ronald Graham (1935–2020) wasn't your typical mathematician. Sure, he was one of the most influential figures in discrete mathematics, working at Bell Labs for 37 years and publishing around 400 papers. But he was also a professional trampolinist who performed in a circus act called "The Bouncing Baers" to pay his way through graduate school.[1]

Graham was also president of the International Jugglers' Association and could juggle up to six balls. His office ceiling at UC San Diego had a large net he could lower and attach to his waist—so when practicing with six or seven balls, any drops would roll right back to him. As he liked to say: "Juggling is a metaphor for doing more things than you have hands to do."[2]

When asked about his namesake number, Graham called it "kind of a joke"—he stumbled upon it while proving a combinatorial theorem using recursive multiple inductions. "When that happens," he explained, "you tend to get large numbers."[3] Understatement of the century.

The Black Hole Problem

Here's a fact that still gives me chills. According to Numberphile:

If you were to try to memorize each digit of Graham's number, your head would sooner turn into a black hole before you were done. This happens because a black hole the size of your head stores less information than what it would take to store all of the digits of Graham's number.

Read that again. Your brain would literally collapse into a black hole before you could memorize this number. This isn't hyperbole—it's a consequence of the Bekenstein bound, which limits how much information can be stored in a finite region of space.

How do we define Graham's number?

We can't use ordinary notation—there simply isn't enough paper in the universe. Instead, we'll use Knuth's up-arrow notation, a system designed for expressing hyperoperations. If you haven't seen it before, I wrote about it here.

To build Graham's number, we start at level 1:

$$ G_1 = 3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow 3 $$

Those four arrows represent hexation—a hyperoperation so powerful that it makes exponentiation look like addition. Let's build up to it step by step.

Exponentiation: \(3\uparrow3\)

No big deal:

$$ 3\uparrow3 = 3^3 = 27 $$

Tetration: \(3\uparrow\uparrow3\)

This is a power tower—exponents stacked on exponents:

$$ 3\uparrow\uparrow3 = 3^{3^3} = 3^{27} = 7{,}625{,}597{,}484{,}987 $$

We're already at 7.6 trillion. Things are heating up.

Pentation: \(3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow3\)

Pentation is iterated tetration—a tower of power towers:

$$ 3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow3 = 3\uparrow\uparrow(3\uparrow\uparrow3) = 3\uparrow\uparrow(7{,}625{,}597{,}484{,}987) $$

This means a power tower of 3s that is 7.6 trillion levels tall:

$$ \left.\begin{aligned} 3^{3^{3^{3^{⋰^{3}}}}} \end{aligned}\right\} \text{ height = 7,625,597,484,987} $$

Stop and think about this. Just counting each 3 in this tower out loud would take tens of thousands of years. And we can't write this number down—there aren't enough particles in the observable universe ($10^{80}$) to represent each digit.

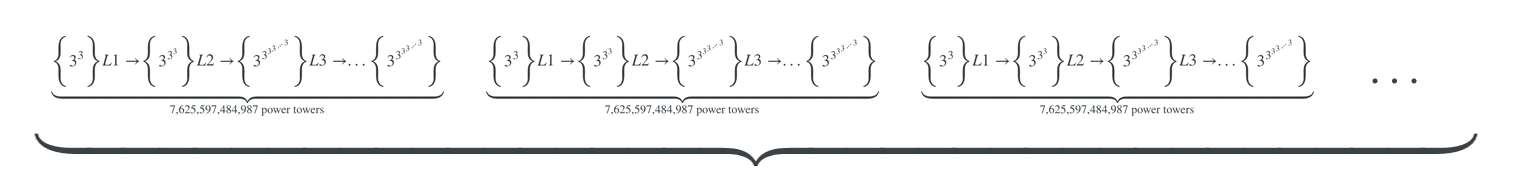

Hexation: \(3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow 3\)

Hexation is iterated pentation. The result of one pentation tower determines how many more towers to compute:

$$ 3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow3 = 3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow(3\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow3) $$

This creates a cascading sequence of incomprehensible growth:

This monstrous result is \(G_1\).

Building Graham's Number

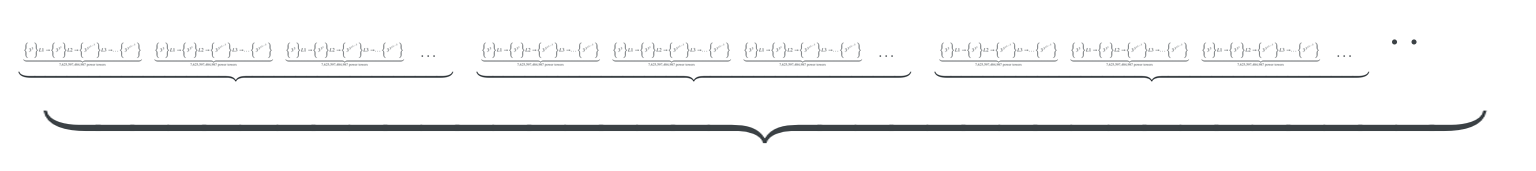

Now here's where it gets truly insane. We use \(G_1\) to define the number of arrows for \(G_2\):

$$ G_2 = \underbrace{3\uparrow\uparrow \cdots \uparrow\uparrow 3}_{G_1 \text{ arrows}} $$

Remember: each additional arrow creates an explosion in size. Going from 4 arrows to 5 arrows is incomprehensibly more powerful than going from 3 to 4. And \(G_1\) already has a number of arrows we can't even write down.

Then \(G_2\) becomes the number of arrows for \(G_3\):

$$ G_3 = \underbrace{3\uparrow\uparrow \cdots \uparrow\uparrow 3}_{G_2 \text{ arrows}} $$

This keeps going: \(G_4\), \(G_5\), \(G_6\)... each one using the previous result as its number of arrows.

Graham's number is \(G_{64}\).

$$ G_{64} = \underbrace{3\uparrow\uparrow \cdots \uparrow\uparrow 3}_{G_{63} \text{ arrows}} $$

We iterate this process sixty-four times.

Why Does This Number Exist? Ramsey Theory

Graham's number isn't mathematical showboating—it emerged from a real problem in Ramsey theory:

Connect each pair of geometric vertices of an n-dimensional hypercube to obtain a complete graph on \(2^n\) vertices. Color each edge either red or blue. What is the smallest value of n for which every such coloring contains at least one single-colored complete subgraph on four coplanar vertices?

In 1971, Ronald Graham and Bruce Rothschild proved that a solution exists with an upper bound equal to Graham's number. The actual answer is believed to be much smaller—somewhere between 13 and \(2\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow6\) (proven in 2014)—but Graham's number was a legitimate bound.[4]

In 1980, the Guinness Book of World Records recognized it as the largest number ever used in a serious mathematical proof.

What We Actually Know About Graham's Number

We can't compute Graham's number, but we can determine some of its properties. Remarkably, we know its last 500 digits:

...02425950695064738395657479136519351798334535362521430035401260267716226721604198106522631693551887803881448314065252616878509555264605107117200099709291249544378887496062882911725063001303622934916080254594614945788714278323508292421020918258967535604308699380168924988926809951016905591995119502788717830837018340236474548882222161573228010132974509273445945043433009010969280253527518332898844615089404248265018193851562535796399618993967905496638003222348723967018485186439059104575627262464195387

I find it delightful that we can know the ending of a number whose full representation exceeds the information capacity of the observable universe.

Where Graham's Number Sits

In the fast-growing hierarchy, Graham's number sits around:

$$ \text{Graham's Number} < f_{\omega+1}(64) $$

But Wait—There Are Even Bigger Numbers

Graham's number is famous, but it's been utterly eclipsed. TREE(3), arising from a problem about trees in graph theory, is so much larger that Graham's number is essentially zero by comparison.[5]

How much larger? Consider this: even if you computed \(G_{G_{G_{...}}}\) with Graham's number levels of nesting, you'd still be nowhere close to TREE(3). It exists in an entirely different realm of magnitude. And SSCG(3) is larger still—much larger than TREE(TREE(...TREE(3)...)) nested TREE(3) times.[6]

The rabbit hole goes infinitely deep.

Learn More

Numberphile has an excellent video on Graham's number that I highly recommend: